Dance This Mess Around: A Mystery

What do John Cage, Coin Tosses, and a Hippy Hippy Shake have to do with the B-52's classic 1978 jam?

Probably nothing.

But maybe everything.

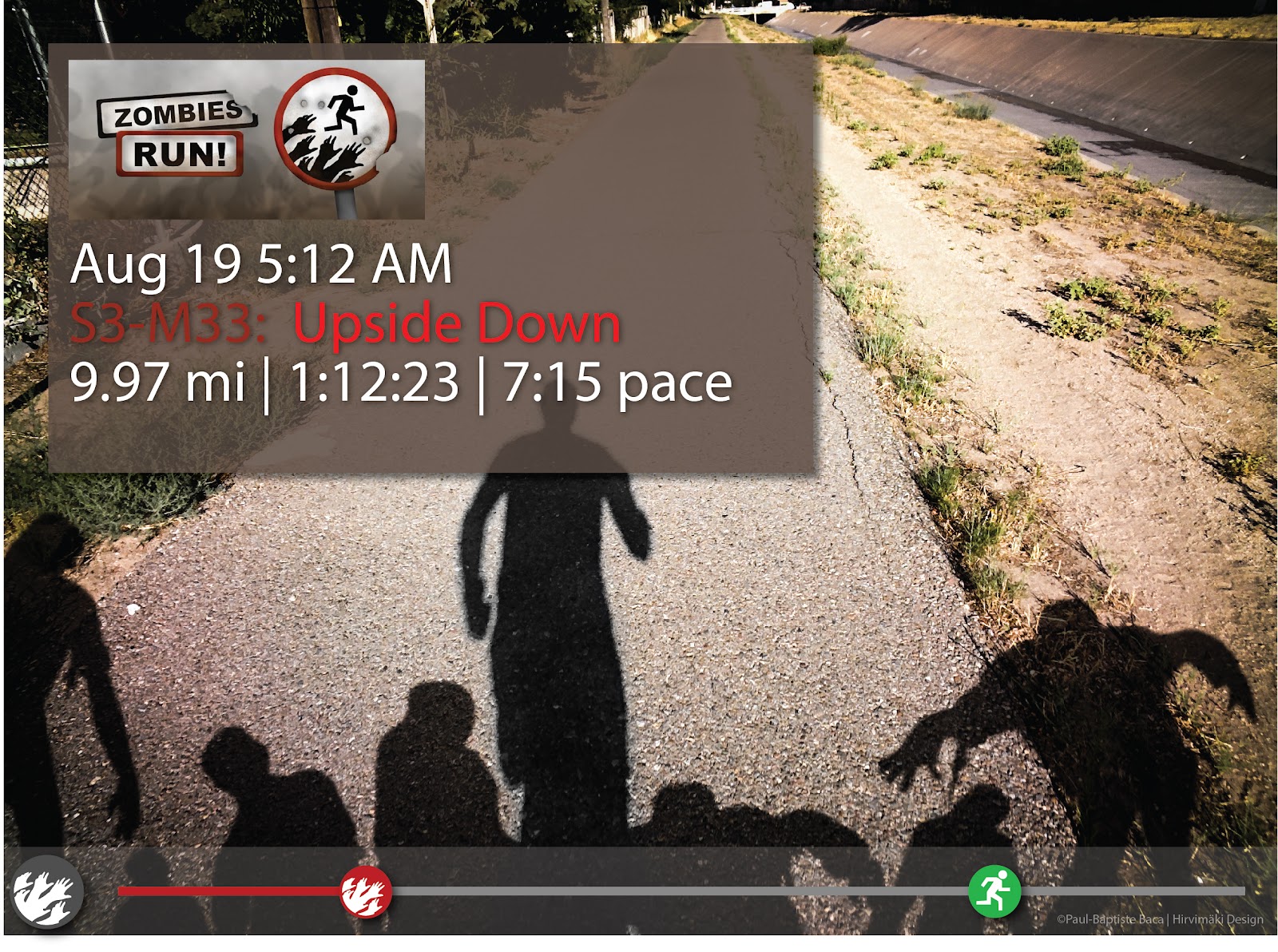

This all started on a run.

(Yes, I'm running again. I'll never be the runner I was before the injury, but I can still get out there and move slightly faster than a turtle. Sometimes. And it gives me time to think.)

I make playlists for my runs. I enjoy the metronomic quality of running to a beat. When I can hit my Goldilocks Zone for a beat it just makes my run that much more awesome. A good tempo keeps me moving not too slow and not too fast. Thursday night I was assembling a new playlist for the following morning. My modus operandi is to scroll through song lists - other people's curated "Best Songs for Running" or "80s Pop for a Good Workout" for example - and when a song catches my fancy I'll play a snippet of it to visualise how it'd be for running. (This is imperfect, of course.) I was nostalgically pleased to see the B-52's "Dance This Mess Around" on a list. It's a great song. The beat is just right. And I had not listened to it in years. Onto my playlist it went. I slept.

5:30 AM. I'm running. "One Way Or Another." Excellent start. "N.W.O." Nice follow-up with lots of energy. "Ready To Go." Right in the groove! And then "Dance This Mess Around." Now, I’ll admit, I apparently hadn't fully thought its inclusion through. Sure, excellent energy. Near perfect beat. But midway into the song Fred Schneider belts out, "They do all sixteen dances!"

Oh no...

I was seized by the compulsion to actually do the dances that Fred was shouting about. It's hard to run while doing a full-body Camel Walk. It is even harder to do so with anything resembling dignity.

But my ridiculousness in attempting the Shug-A-Loo wasn't the real problem. The problem was this:

Fred only names eight dances.

EIGHT!

He claims there are sixteen.

Why? Why name eight if you say there are sixteen? Why the discrepancy?

And here is where peeking inside my head can be...strange. This brain o' mine is a wonderous place if you like weird. There's a special room in there where oddball neurons play mad-scientist Build-a-Bear with music history, postmodern dance, and punk lore. It's like the lovechild of a footnote from Greil Marcus and an interpretive dance performed on a UFO landing pad.

I began to wonder, when you consider how much of the B-52's early style was rooted in kitsch, chaos, and Dadaist performance, what if they were channeling chance-determined expressive behavior under all that beehive-and-cabana glamour?

Deliciously absurd. But maybe not so absurd after all.

Hear me out. Sure, it's probably not the canonical answer. But is there one? The B-52's were the band that turned thrift store pop culture into surrealist theater, after all. So why not a secret nod to avant-garde mid-century dance theory?

What if the point is...that none of the sixteen dances are actually named at all?

What if, in true B-52's contrarian spirit, the dances you do hear are not part of the “real” sixteen? That's when a theory began to take shape, strange, glorious, and completely plausible if you live in my head. (There's a disco mirror ball in there.)

A Little Background: Sixteen Dances (1951)

Before the B-52's ever danced this mess around, there was another "Sixteen Dances."

It’s the name of a collaborative work by composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham, first performed on January 21, 1951. It was a landmark piece, and the first time Cunningham used chance operations in his choreography. Cage, as usual, mirrored the method in the music itself.

(See? Lots of random boxes are in storage up here.)

The work consists of 16 short dances performed by Cunningham and three other dancers. Each segment corresponds to one of nine permanent emotions from Indian classical aesthetics: four light, four dark, and one pervasive emotion, tranquility. The first seven emotions were expressed through solos, with the last two danced as a duet and quartet.

Cunningham explained the structure this way:

"The choreography was concerned with expressive behavior, in this case the nine permanent emotions of Indian classical aesthetics, four light and four dark with tranquility the ninth and pervading one. The structure for the piece was to have each of the dances involved with a specific emotion followed by an interlude. Although the order was to alternate light and dark, it didn't seem to matter whether Sorrow or Fear came first, so I tossed a coin."

In one segment, Cunningham used charts of isolated movements for each dancer and let chance determine how those movements were strung together. Cage's score for piano and small orchestra followed similar logic, with sound material replaced mid-piece according to pre-determined procedures.

It was rigorous, radical, and weirdly rhythmic.

Sound familiar?

Well, it does to my brain.

Now Enter: The B-52's

Fast-forward to 1979. The B-52's, freshly emerged from Athens, Georgia, are blowing minds and glittering up garage rock with go-go grooves, post-punk swagger, and thrift-store chic. They've got the energy of a dance party and the DNA of a Dada performance piece. Beneath the wigs and kitsch lies serious art-school subversion.

Which brings us back to the mystery of the 16 dances.

What if "Dance This Mess Around" isn't just a cheeky nostalgia trip through invented dance crazes, but a reinterpretation of Cage and Cunningham's seminal 1951 work, smuggled onto the dance floor in platform shoes?

The Theory: Dances Within Dances

Let’s break it down:

The band performs all 16 of Cage and Cunningham's dances, honoring the original structure, emotional solos, a duet, a quartet, and interludes guided by chance. But now, it's reimagined through sequined chaos, staccato keyboard stabs, and Cindy Wilson's volcanic vocals.Not content to just re-do something already done, they follow the Cage and Cunningham 16 with four original, named dances: the Shug-A-Loo, the Shy Tuna, the Camel Walk, and the Hip-O-Crit. These are determined by chance, just as Cunningham once flipped coins to decide the order of emotional expression.

Another "hippy hippy forward," another shake, another ending.

Still not good enough. A third attempt looms. But Cindy Wilson, seeing improvement and trying to encourage the now-sweaty dancers, asks:

"Doesn't that make you feel much better?"

Fred, ever the perfectionist (or trapped in a Cagean feedback loop), pretends not to hear her, "Huh?"

Before round three can begin, Cindy calls out: "Stop!" And the band releases a collective sigh of cathartic agreement:

"Yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah!"

So... Did They Really Dance This Mess Around?

Maybe not literally. But this theory makes the song more than a retro dance track. It becomes a recursive performance piece, a looping burst of ecstatic nonsense and structural parody. It channels "Sixteen Dances" through polyester and fuzzed-out organs, revealing the experimental beneath the exuberant.

The looping structure of the song (Fred’s insistence on "doing 'em right," the repeated yelps of "yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah!") does bear some resemblance to Cage's recursive and non-linear structures. Cindy Wilson’s question, "Say, doesn't that make you feel a lot better?" is a kind of Brechtian interjection, like she’s breaking character to appeal to the audience. (Or the choreographer. Or both.)

It's not just camp. It's concept.

So the next time someone asks, "What are the 16 dances in 'Dance This Mess Around'?" you can smile and say:

"The sixteen were composed by John Cage and choreographed by Merce Cunningham. The additional eight were thrown in as red herrings, determined by coin toss and performed in wigs."

Mystery solved? OK, probably not. But maybe. I bet this would at least get best lecture-performance at the next MoMA retrospective.

Either way, I'm claiming credit the next time someone stages "Dance This Mess Around" as a Cunningham reconstruction in sequins and yellow Day-Glo.

Comments